Absolute Advantage

A nation has an absolute advantage if (1) it’s the only source of a particular product or (2) it can make more of a product using the same amount of or fewer resources than other countries. Because of climate and soil conditions, for example, Brazil has an absolute advantage in coffee beans and France has an absolute advantage in wine production. Unless, however, an absolute advantage is based on some limited natural resource, it seldom lasts. That’s why there are few examples of absolute advantage in the world today. Even France’s dominance of worldwide wine production, for example, is being challenged by growing wine industries in Italy, Spain, and the United States.

Comparative Advantage

How can we predict, for any given country, which products will be made and sold at home, which will be imported, and which will be exported? This question can be answered by looking at the concept of comparative advantage, which exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost compared to another nation. But what’s an opportunity cost? Opportunity costs are the products that a country must decline to make in order to produce something else. When a country decides to specialize in a particular product, it must sacrifice the production of another product.

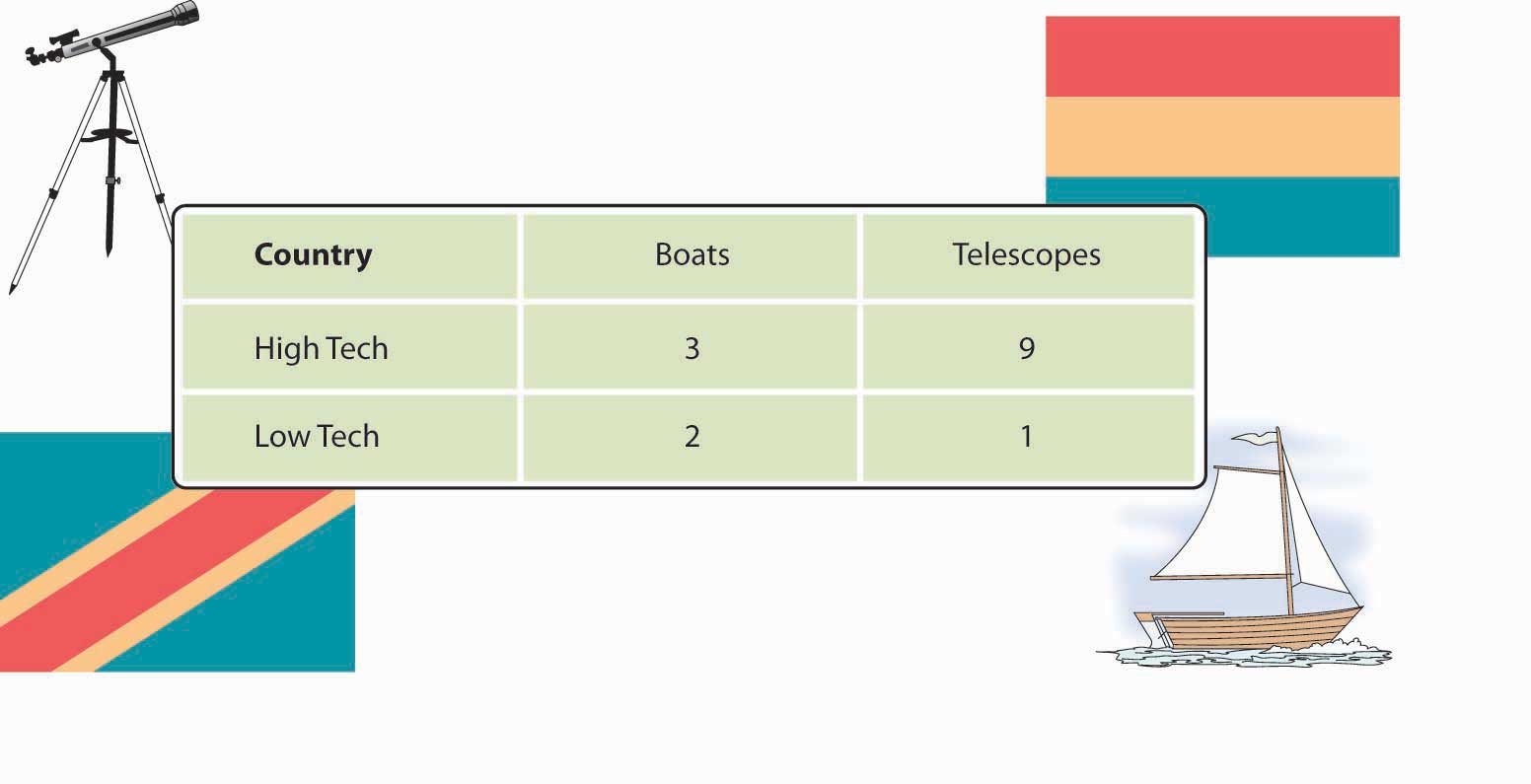

Let’s simplify things by imagining a world with only two countries—the Republic of High Tech and the Kingdom of Low Tech. Each country knows how to make two and only two products: wooden boats and telescopes. Each country spends half its resources (labor and capital) on each good. Figure 3.3 “Comparative Advantage in the Techs” shows the daily output for both countries. (They’re not highly productive, as we’ve imagined two very small countries.)

Figure 3.3 Comparative Advantage in the Techs

First, note that High Tech has an absolute advantage in both boats and telescopes: it can make more boats (three versus two) and more telescopes (nine versus one) than Low Tech can with the same resources. So, why doesn’t High Tech make all the boats and all the telescopes needed for bothcountries? Because it lacks sufficient resources and must, therefore, decide how much of its resources to devote to each of the two goods. Assume, for example, that each country could devote 100 percent of its resources on either of the two goods. Start with boats. If both countries spend all their resources on boats (and make no telescopes), here’s what happens:

- High Tech makes, for example, three more boats but gives up the opportunity to make the nine telescopes; thus the opportunity cost of making each boat is three telescopes (9 ÷ 3 = 3).

- Low Tech makes, for example, two more boats but gives up the opportunity to make one telescope; thus the opportunity cost of making each boat is half a telescope (1 ÷ 2 = 1/2).

- Low Tech, therefore, enjoys a lower opportunity cost: Because it must give up less to make the extra boats, it has a comparative advantage for boats. And because it’s better—that is, more efficient—at making boats than at making telescopes, it should specialize in boat making.

Now to telescopes. Here’s what happens if each country spends all its time making telescopes and makes no boats:

- High Tech makes, for example, nine more telescopes but gives up the opportunity to make three boats; thus, the opportunity cost of making each telescope is one third of a boat (3 ÷ 9 = 1/3).

- Low Tech makes, for example, one more telescope but gives up the opportunity to make two boats; thus, the opportunity cost of making each telescope is two boats (2 ÷ 1 = 2).

- In this case, High Tech has the lower opportunity cost: Because it had to give up less to make the extra telescopes, it enjoys a comparative advantage for telescopes. And because it’s better—more efficient—at making telescopes than at making boats, it should specialize in telescope making.

Each country will specialize in making the good for which it has a comparative advantage—that is, the good that it can make most efficiently, relative to the other country. High Tech will devote its resources to telescopes (which it’s good at making), and Low Tech will put its resources into boat making (which it does well). High Tech will export its excess telescopes to Low Tech, which will pay for the telescopes with the money it earns by selling its excess boats to High Tech. Both countries will be better off.

Things are a lot more complex in the real world, but, generally speaking, nations trade to exploit their advantages. They benefit from specialization, focusing on what they do best, and trading the output to other countries for what they do best. The United States, for instance, is increasingly an exporter of knowledge-based products, such as software, movies, music, and professional services (management consulting, financial services, and so forth). America’s colleges and universities, therefore, are a source of comparative advantage, and students from all over the world come to the United States for the world’s best higher-education system.

France and Italy are centers for fashion and luxury goods and are leading exporters of wine, perfume, and designer clothing. Japan’s engineering expertise has given it an edge in such fields as automobiles and consumer electronics. And with large numbers of highly skilled graduates in technology, India has become the world’s leader in low-cost, computer-software engineering.

Source:

“Business in a Global Environment”, chapter 3 from the book An Introduction to Business (v. 1.0), curated by Andy Schmitz on http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/an-introduction-to-business-v1.0/s07-business-in-a-global-environme.html