Trade and monetary groupings and composition⊕

Category: Academic Theory

A signpost to useful information on the academic theories and frameworks used in the international business and global strategy literature.

Classification of Individual economies and territories

Do mature industries have their own innovation dynamics?

This study investigates the creation of the thermoplastic vulcanizates industry as an example of innovation constructed within a mature industry, in this case, the petrochemicals industry. A characterization is made of this innovation process, identifying the technological and organizational dimensions that are inherent to it as well as the nature of the competencies and resources mobilized by the companies involved in the innovation.⊕

(2006). Do mature industries have their own innovation dynamics?: A reflection based on the development of the thermoplastic vulcanizates industry. Polímeros, 16(2), 12-19. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-14282006000200005

The Emergence of a Powerful State within a Neo-liberal conversation

Julian Assange is now free. The whole episode of imprisoning him on rape charges has turned him into a sort of modern day anti- establishment hero. Many have seen it as the machinations of powerful state actors willing to bend rules to nail Assange down, no matter how guilty he is of the actual deed. This then brings us to debate of the morality behind such actions by a nation that has prided itself on being so full of democratic ideals that it dares to lecture to other states like China and the Middle East. What is so democratic about stifling the freedom of a man who gave us a glimpse into the workings of the diplomatic corps. Most governments have denied that the wiki leak cables have any ounce of truth in them. If it was the truth, Governments should have left these rumours take its natural course and die on its own. Do we not witness many examples of stories particularly those involved with celebrities go down this route and die out? To have gone after Julian Assange in this fashion has added more mystique to his persona and created more distrust of the way democratic and neo-liberalistic govts manage the freedom of the Individual. We are no different from any of the states run by Tinpot dictators. Even India, hailed as a bastion of democracy has been guilty of state supported suppression of personal freedom (the Emergency Era of Indira Gandhi). What then makes democratic states different from other systems of Government if its citizens do not have personal choices? I think what we are seeing is a mixture of several forces trying to turn a simple act of leaking information into an media circus. The first force is that of Individuals trying to have their 15minutes of fame without any regard to the effect their actions will have on an ordered global political system. The second force is that of State actors trying to exceed their moral brief in trying to suppress the first force. What both forces forget is that their fight is being played out in a fast moving interconnected world where we – the people are watching and forming perceptions, some of which verge on extremely dangerous responses like cyber attacks and more conventional forms of organised disruptions. Do we need our world to be turned upside down by these careless acts of stupidity by both states and individuals? Do we need a nanny state to dictate every personal action?

Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage

Tariff

The most common way to protect one’s economy from import competition is to implement a tariff: a tax on imports. Generally speaking, a tariff is any tax or fee collected by a government. Sometimes the term “tariff” is used in a nontrade context, as in railroad tariffs. However, the term is much more commonly used to refer to a tax on imported goods. Read more

Source:Policy and Theory of International Trade from http://2012books.lardbucket.org

What Is Economics?

To appreciate how a business functions, we need to know something about the economic environment in which it operates. We begin with a definition of economics and a discussion of the resources used to produce goods and services.

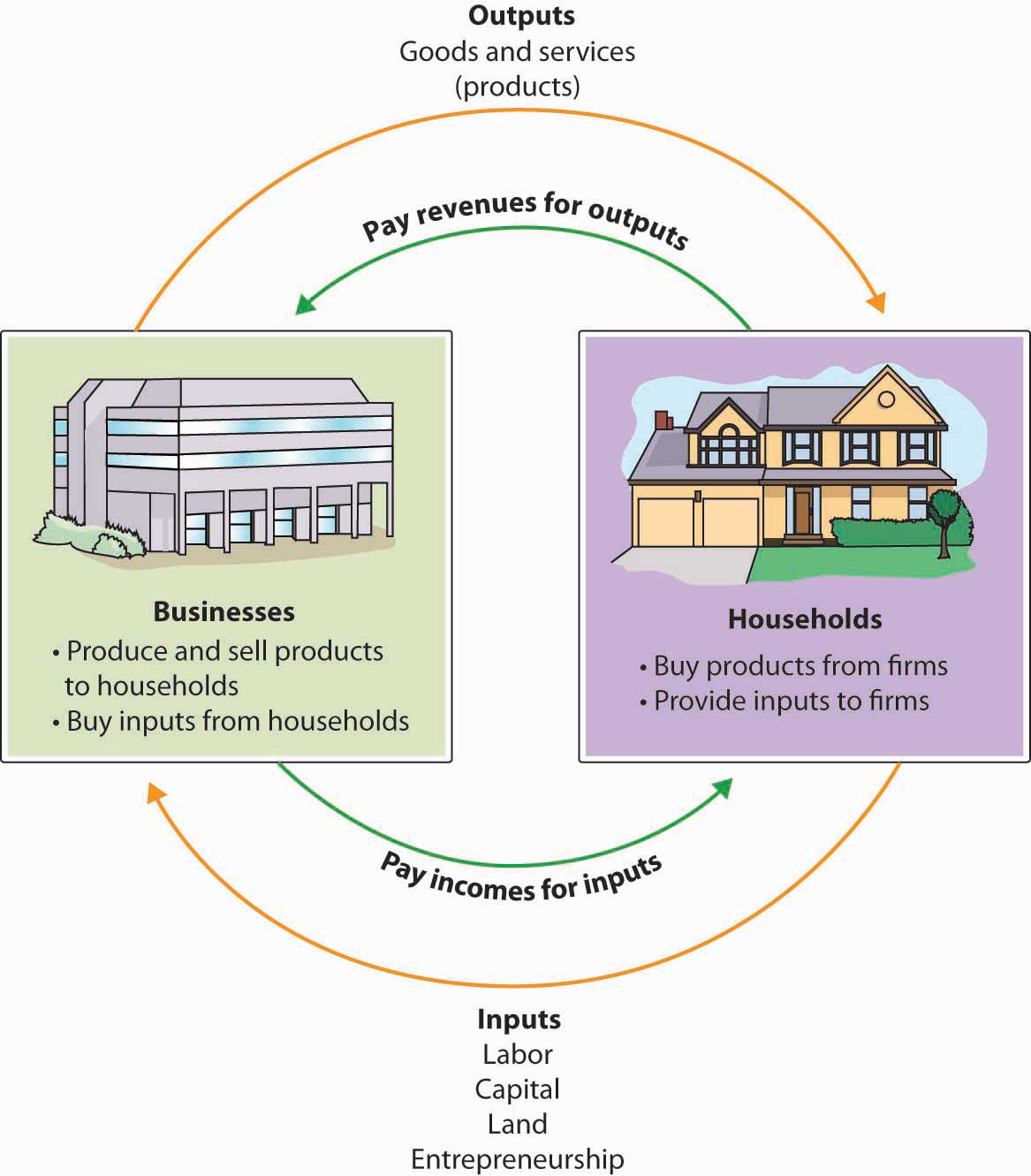

Resources: Inputs and Outputs

Economics is the study of how scarce resources are used to produce outputs—goods and services—to be distributed among people. Resources are the inputs used to produce outputs. Resources may include any or all of the following:

- Land and other natural resources

- Labor (physical and mental)

- Capital, including buildings, equipment, and money

- Entrepreneurship

Resources are combined to produce goods and services. Land and natural resources provide the needed raw materials. Labor transforms raw materials into goods and services. Capital (equipment, buildings, vehicles, cash, and so forth) are needed for the production process. Entrepreneurship provides the skill and creativity needed to bring the other resources together to capitalize on an idea.

Because a business uses resources to produce things, we also call these resources factors of production. The factors of production used to produce a shirt would include the following:

- The land that the shirt factory sits on, the electricity used to run the plant, and the raw cotton from which the shirts are made

- The laborers who make the shirts

- The factory and equipment used in the manufacturing process, as well as the money needed to operate the factory

- The entrepreneurship skill used to coordinate the other resources to initiate the production process

Input and Output Markets

Many of the factors of production (or resources) are provided to businesses by households. For example, households provide businesses with labor (as workers), land and buildings (as landlords), and capital (as investors). In turn, businesses pay households for these resources by providing them with income, such as wages, rent, and interest. The resources obtained from households are then used by businesses to produce goods and services, which are sold to the same households that provide businesses with revenue. The revenue obtained by businesses is then used to buy additional resources, and the cycle continues. This circular flow is described in Figure 1.4 “The Circular Flow of Inputs and Outputs”, which illustrates the dual roles of households and businesses:

- Households not only provide factors of production (or resources) but also consume goods and services.

- Businesses not only buy resources but also produce and sell both goods and services.

Figure 1.4 The Circular Flow of Inputs and Outputs

The Questions Economists Ask

Economists study the interactions between households and businesses and look at the ways in which the factors of production are combined to produce the goods and services that people need. Basically, economists try to answer three sets of questions:

- What goods and services should be produced to meet consumers’ needs? In what quantity? When should they be produced?

- How should goods and services be produced? Who should produce them, and what resources, including technology, should be combined to produce them?

- Who should receive the goods and services produced? How should they be allocated among consumers?

Economic Systems

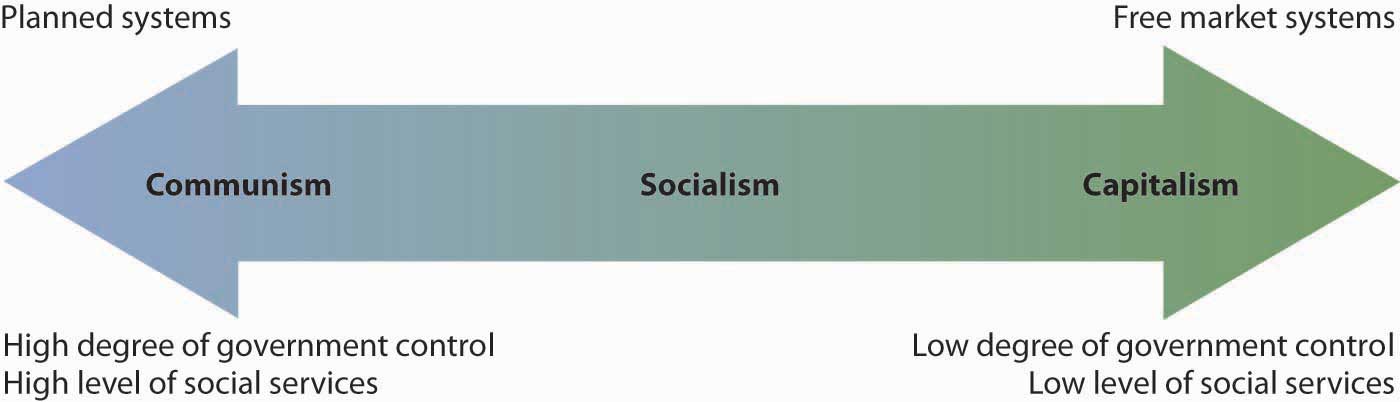

The answers to these questions depend on a country’s economic system—the means by which a society (households, businesses, and government) makes decisions about allocating resources to produce products and about distributing those products. The degree to which individuals and business owners, as opposed to the government, enjoy freedom in making these decisions varies according to the type of economic system. Generally speaking, economic systems can be divided into two systems: planned systems and free market systems.

Planned Systems

In a planned system, the government exerts control over the allocation and distribution of all or some goods and services. The system with the highest level of government control is communism. In theory, a communist economy is one in which the government owns all or most enterprises. Central planning by the government dictates which goods or services are produced, how they are produced, and who will receive them. In practice, pure communism is practically nonexistent today, and only a few countries (notably North Korea and Cuba) operate under rigid, centrally planned economic systems.

Under socialism, industries that provide essential services, such as utilities, banking, and health care, may be government owned. Other businesses are owned privately. Central planning allocates the goods and services produced by government-run industries and tries to ensure that the resulting wealth is distributed equally. In contrast, privately owned companies are operated for the purpose of making a profit for their owners. In general, workers in socialist economies work fewer hours, have longer vacations, and receive more health, education, and child-care benefits than do workers in capitalist economies. To offset the high cost of public services, taxes are generally steep. Examples of socialist countries include Sweden and France.

Free Market System

The economic system in which most businesses are owned and operated by individuals is the free market system, also known as capitalism. As we will see next, in a free market, competition dictates how goods and services will be allocated. Business is conducted with only limited government involvement. The economies of the United States and other countries, such as Japan, are based on capitalism.

How Economic Systems Compare

In comparing economic systems, it’s helpful to think of a continuum with communism at one end and pure capitalism at the other, as in Figure 1.5 “The Spectrum of Economic Systems”. As you move from left to right, the amount of government control over business diminishes. So, too, does the level of social services, such as health care, child-care services, social security, and unemployment benefits.

Figure 1.5 The Spectrum of Economic Systems

Mixed Market Economy

Though it’s possible to have a pure communist system, or a pure capitalist (free market) system, in reality many economic systems are mixed. A mixed market economy relies on both markets and the government to allocate resources. We’ve already seen that this is what happens in socialist economies in which the government controls selected major industries, such as transportation and health care, while allowing individual ownership of other industries. Even previously communist economies, such as those of Eastern Europe and China, are becoming more mixed as they adopt capitalistic characteristics and convert businesses previously owned by the government to private ownership through a process called privatization.

The U.S. Economic System

Like most countries, the United States features a mixed market system: though the U.S. economic system is primarily a free market system, the federal government controls some basic services, such as the postal service and air traffic control. The U.S. economy also has some characteristics of a socialist system, such as providing social security retirement benefits to retired workers.

The free market system was espoused by Adam Smith in his book The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776.According to many scholars, The Wealth of Nations not only is the most influential book on free-market capitalism but remains relevant today. According to Smith, competition alone would ensure that consumers received the best products at the best prices. In the kind of competition he assumed, a seller who tries to charge more for his product than other sellers won’t be able to find any buyers. A job-seeker who asks more than the going wage won’t be hired. Because the “invisible hand” of competition will make the market work effectively, there won’t be a need to regulate prices or wages.

Almost immediately, however, a tension developed among free market theorists between the principle of laissez-faire—leaving things alone—and government intervention. Today, it’s common for the U.S. government to intervene in the operation of the economic system. For example, government exerts influence on the food and pharmaceutical industries through the Food and Drug Administration, which protects consumers by preventing unsafe or mislabeled products from reaching the market.

To appreciate how businesses operate, we must first get an idea of how prices are set in competitive markets. Thus, the next section begins by describing how markets establish prices in an environment of perfect competition.

Source: An Introduction to Business (v. 1.0) from http://2012books.lardbucket.org

Market Attractiveness

Four key factors in selecting global markets are (a) a market’s size and growth rate, (b) a particular country or region’s institutional contexts, (c) a region’s competitive environment, and (d) a market’s cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic distance from other markets the company serves.

Market Size and Growth Rate

There is no shortage of country information for making market portfolio decisions. A wealth of country-level economic and demographic data are available from a variety of sources including governments, multinational organizations such as the United Nations or the World Bank, and consulting firms specializing in economic intelligence or risk assessment. However, while valuable from an overall investment perspective, such data often reveal little about the prospects for selling products or services in foreign markets to local partners and end users or about the challenges associated with overcoming other elements of distance. Yet many companies still use this information as their primary guide to market assessment simply because country market statistics are readily available, whereas real product market information is often difficult and costly to obtain.

What is more, a country or regional approach to market selection may not always be the best. Even though Theodore Levitt’s vision of a global market for uniform products and services has not come to pass, and global strategies exclusively focused on the “economics of simplicity” and the selling of standardized products all over the world rarely pay off, research increasingly supports an alternative “global segmentation” approach to the issue of market selection, especially for branded products. In particular, surveys show that a growing number of consumers, especially in emerging markets, base their consumption decisions on attributes beyond direct product benefits, such as their perception of the global brands behind the offerings.

Specifically, research by John Quelch and others suggests that consumers increasingly evaluate global brands in “cultural” terms and factor three global brand attributes into their purchase decisions: (a) what a global brand signals about quality, (b) what a brand symbolizes in terms of cultural ideals, and (c) what a brand signals about a company’s commitment to corporate social responsibility. This creates opportunities for global companies with the right values and the savvy to exploit them to define and develop target markets across geographical boundaries and create strategies for “global segments” of consumers. Specifically, consumers who perceive global brands in the same way appear to fall into one of four groups:

- Global citizens rely on the global success of a company as a signal of quality and innovation. At the same time, they worry whether a company behaves responsibly on issues like consumer health, the environment, and worker rights.

- Global dreamers are less discerning about, but more ardent in their admiration of, transnational companies. They view global brands as quality products and readily buy into the myths they portray. They also are less concerned with companies’ social responsibilities than global citizens.

- Antiglobals are skeptical that global companies deliver higher-quality goods. They particularly dislike brands that preach American values and often do not trust global companies to behave responsibly. Given a choice, they prefer to avoid doing business with global firms.

- Global agnostics do not base purchase decisions on a brand’s global attributes. Instead, they judge a global product by the same criteria they use for local brands.Quelch (2003, August); Holt, Quelch, and Taylor (2004, September).

Companies that use a “global segment” approach to market selection, such as Coca-Cola, Sony, or Microsoft, to name a few, therefore must manage two dimensions for their brands. They must strive for superiority on basics like the brand’s price, performance, features, and imagery, and, at the same time, they must learn to manage brands’ global characteristics, which often separate winners from losers. A good example is provided by Samsung, the South Korean electronics maker. In the late 1990s, Samsung launched a global advertising campaign that showed the South Korean giant excelling, time after time, in engineering, design, and aesthetics. By doing so, Samsung convinced consumers that it successfully competed directly with technology leaders across the world, such as Nokia and Sony. As a result, Samsung was able to change the perception that it was a down-market brand, and it became known as a global provider of leading-edge technologies. This brand strategy, in turn, allowed Samsung to use a global segmentation approach to making market selection and entry decisions.

Source:Global Strategy from http://2012books.lardbucket.org

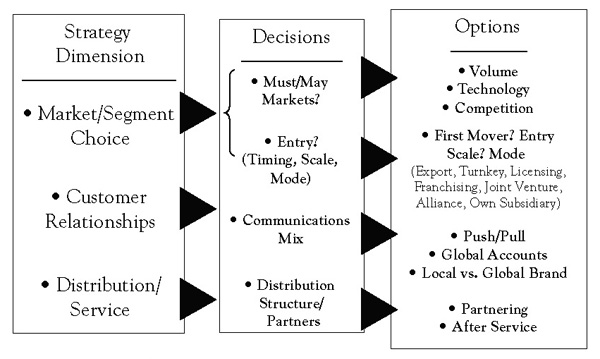

Target Market Selection

Few companies can afford to enter all markets open to them. Even the world’s largest companies such as General Electric or Nestlé must exercise strategic discipline in choosing the markets they serve. They must also decide when to enter them and weigh the relative advantages of a direct or indirect presence in different regions of the world. Small and midsized companies are often constrained to an indirect presence; for them, the key to gaining a global competitive advantage is often creating a worldwide resource network through alliances with suppliers, customers, and, sometimes, competitors. What is a good strategy for one company, however, might have little chance of succeeding for another.

Figure 5.1 Market Participation

The track record shows that picking the most attractive foreign markets, determining the best time to enter them, and selecting the right partners and level of investment has proven difficult for many companies, especially when it involves large emerging markets such as China. For example, it is now generally recognized that Western carmakers entered China far too early and overinvested, believing a “first-mover advantage” would produce superior returns. Reality was very different. Most companies lost large amounts of money, had trouble working with local partners, and saw their technological advantage erode due to “leakage.” None achieved the sales volume needed to justify their investment.

Even highly successful global companies often first sustain substantial losses on their overseas ventures, and occasionally have to trim back their foreign operations or even abandon entire countries or regions in the face of ill-timed strategic moves or fast-changing competitive circumstances. Not all of Wal-Mart’s global moves have been successful, for example—a continuing source of frustration to investors. In 1999, the company spent $10.8 billion to buy British grocery chain Asda. Not only was Asda healthy and profitable, but it was already positioned as “Wal-Mart lite.” Today, Asda is lagging well behind its number-one rival, Tesco. Even though Wal-Mart’s UK operations are profitable, sales growth has been down in recent years, and Asda has missed profit targets for several quarters running and is in danger of slipping further in the UK market.

This result comes on top of Wal-Mart’s costly exit from the German market. In 2005, it sold its 85 stores there to rival Metro at a loss of $1 billion. Eight years after buying into the highly competitive German market, Wal-Mart executives, accustomed to using Wal-Mart’s massive market muscle to squeeze suppliers, admitted they had been unable to attain the economies of scale it needed in Germany to beat rivals’ prices, prompting an early and expensive exit.

What makes global market selection and entry so difficult? Research shows there is a pervasive the-grass-is-always-greener effect that infects global strategic decision making in many, especially globally inexperienced, companies and causes them to overestimate the attractiveness of foreign markets.Ghemawat (2001). As noted in Chapter 1 “Competing in a Global World”, “distance,” broadly defined, unless well-understood and compensated for, can be a major impediment to global success: cultural differences can lead companies to overestimate the appeal of their products or the strength of their brands; administrative differences can slow expansion plans, reduce the ability to attract the right talent, and increase the cost of doing business; geographic distance impacts the effectiveness of communication and coordination; and economic distance directly influences revenues and costs.

A related issue is that developing a global presence takes time and requires substantial resources. Ideally, the pace of international expansion is dictated by customer demand. Sometimes it is necessary, however, to expand ahead of direct opportunity in order to secure a long-term competitive advantage. But as many companies that entered China in anticipation of its membership in the World Trade Organization have learned, early commitment to even the most promising long-term market makes earning a satisfactory return on invested capital difficult. As a result, an increasing number of firms, particularly smaller and midsized ones, favor global expansion strategies that minimize direct investment. Strategic alliances have made vertical or horizontal integration less important to profitability and shareholder value in many industries. Alliances boost contribution to fixed cost while expanding a company’s global reach. At the same time, they can be powerful windows on technology and greatly expand opportunities to create the core competencies needed to effectively compete on a worldwide basis.

Finally, a complicating factor is that a global evaluation of market opportunities requires a multidimensional perspective. In many industries, we can distinguish between “must” markets—markets in which a company must compete in order to realize its global ambitions—and “nice-to-be-in” markets—markets in which participation is desirable but not critical. “Must” markets include those that are critical from a volume perspective, markets that define technological leadership, and markets in which key competitive battles are played out. In the cell phone industry, for example, Motorola looks to Europe as a primary competitive battleground, but it derives much of its technology from Japan and sales volume from the United States.

Source:Global Strategy from http://2012books.lardbucket.org

What Is a Global Corporation?

One could argue that a global company must have a presence in all major world markets—Europe, the Americas, and Asia. Others may define globality in terms of how globally a company sources, that is, how far its supply chain reaches across the world. Still other definitions use company size, the makeup of the senior management team, or where and how it finances its operations as their primary criterion.

Gupta, Govindarajan, and Wang suggest we define corporate globality in terms of four dimensions: a company’s market presence, supply base, capital base, and corporate mind-set.Gupta, Govindarajan, and Wang (2008), p. 7 The first dimension—the globalization of market presence—refers to the degree the company has globalized its market presence and customer base. Oil and car companies score high on this dimension. Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, on the other hand, generates less than 30% of its revenues outside the United States. The second dimension—the globalization of the supply base—hints at the extent to which a company sources from different locations and has located key parts of the supply chain in optimal locations around the world. Caterpillar, for example, serves customer in approximately 200 countries around the world, manufactures in 24 of them, and maintains research and development facilities in nine. The third dimension—globalization of the capital base—measures the degree to which a company has globalized its financial structure. This deals with such issues as on what exchanges the company’s shares are listed, where it attracts operating capital, how it finances growth and acquisitions, where it pays taxes, and how it repatriates profits. The final dimension—globalization of the corporate mind-set—refers to a company’s ability to deal with diverse cultures. GE, Nestlé, and Procter & Gamble are examples of companies with an increasingly global mind-set: businesses are run on a global basis, top management is increasingly international, and new ideas routinely come from all parts of the globe.

In the years to come, the list of truly “global” companies—companies that are global in all four dimensions—is likely to grow dramatically. Global merger and acquisition activity continues to increase as companies around the world combine forces and restructure themselves to become more globally competitive and to capitalize on opportunities in emerging world markets. We have already seen megamergers involving financial services, leisure, food and drink, media, automobile, and telecommunications companies. There are good reasons to believe that the global mergers and acquisitions (M&A) movement is just in its beginning stages—the economics of globalization point to further consolidation in many industries. In Europe, for example, more deregulation and the EU’s move toward a single currency will encourage further M&A activity and corporate restructuring.

Source:Global Strategy from http://2012books.lardbucket.org